Post by ÉMILE JAVERT on Mar 17, 2013 13:42:42 GMT -5

At the end of the day you're another day colder

FULL NAME: Émile Javert

NICKNAMES: none

HERITAGE: French

AGE: 52

GROUP: French Government

CANON: Yes

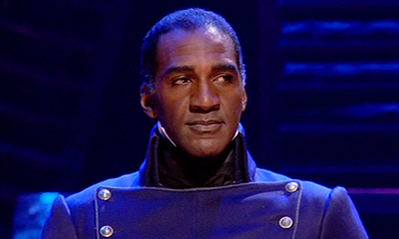

PLAYBY: Norm Lewis

-----

PERSONALITY: Javert is a man whose worldview is black and white, with nothing in between. He took sides early in life and sees himself as firmly planted on the side of the law. When it comes to doing his duty, the quality of his mercy is certainly strained. He is guided by the law, which he sees as absolute and right, not fairness, which is merely subjective and therefore suspect. Although he was born and raised in a jail, or more likely because of it, he is contemptuous of the poor and especially the criminal elements. He is so inflexible that he believes redemption is impossible, forgiveness worthless. His actual understanding of scripture is skewed, though he has most of its verses committed to memory, and he holds the church and its agents— nuns, priests, and their superiors— in the highest respect.

The inspector has been described as the kind of pup that is killed by its mother, for when it grows, it will devour its siblings. In this vein he is like a bulldog, the bulldog as originally bred, not the domesticated adorable bundles of wrinkles. He is stubborn, persistent, and when focused on a goal he dedicates himself wholly to it. He would be blind to anything else, but often that would mean abandoning his current duties, which he isn't willing to do; but given the opportunity, he will pursue it. With criminals he is all sharp edges, curt, commanding, almost joyous in a terrible way so in his element is he. With everyone else he is perhaps not the best of conversationalists and still prone to brusqueness, but it is difficult to draw out the wolf he easily unleashes in the presence of wrongdoers.

His job and what it represents mean the world to him. He always throws himself into his duty wholeheartedly, and although he holds everyone up to an impossible standard, he judges himself by it too. Mistakes are unconscionable, unforgivable. If he fails in any way, he is mortified, and if it is a serious failure he will try to resign, but so far his superiors haven't agreed with his assessment, and so he’s stayed in place. He is always respectful to authority of any kind, regardless of any personal feelings towards the person or institution, and he will obey orders without question.

APPEARANCE: In stature Javert is a poker: long, thin, and sharp, and he carries himself straight like one. His hair is cut short for convenience; his dress, too, is impeccable though simple and, while out of uniform, at least ten years out of fashion. His greatcoat in particular is more patches than original now, but has been meticulously repaired. At all times he appears calm, unflappable; though underneath the surface he may be thrumming with energy, such a small thing as the misplaced buckle of his cravat or a downward glance might be the only indication of unrest. It is in his features though that the true terribleness of Javert’s appearance congregates, where the animals of his nature show themselves. A hound when he is on the scent of a criminal, a tiger when he laughs, and at all times the deep lines of his face put one in mind of the muzzle of some undefined beast. It is a visage that demands respect and recommends avoidance to most.

GOALS: To uphold the law, maintain order, put criminals where they belong— in jail or the galleys, wherever the magistrates choose to send them. On a personal level, to do his duty and never falter, always to represent justice to the best of his ability, and to do the right thing even when he stumbles.

HISTORY: Javert was born into a world where life itself was a war, and he began on the losing side. His mother was a Romani fortune-teller, his father a galley slave. The first room he ever saw was a jail cell. However, a man may be born into sin, but he can rise above it. Javert decided early on that he would side with the law. It was a fateful decision, one that guides all his actions now, drives him through each day. He gets up in the morning and thinks of justice, does his job and metes out justice, comes home and goes to bed and dreams of justice. The law is his life, it is his compass. If there were no law, he could not stand. It is his foundation and if it were to crack, he would fall.

He began his career in the prisons where he grew up. Through hard work and persistence he got himself noticed by the powers that be. He started on the lowest rung of the ladder, becoming an assistant to the very jailor who'd dogged his mother's steps throughout his childhood, but at least it was one foot out of the sewer. And once he reached the sunlight, he never looked back. Javert eventually became a guard at the Bagne of Toulon, a prison where the convicts did hard labor. There he had the opportunity to witness the extraordinary strength of one prisoner in particular, numbered 24601. This criminal, who in civilian life had borne the name Jean Valjean, was imprisoned for stealing a loaf of bread, his original sentence of five years extended to nineteen for trying to escape. When his time for parole came up, Javert was the official who sent him on his way, and the guard made it clear his beliefs— once a criminal, always a criminal.

Five years later, Javert had climbed a few more rungs and was appointed police inspector in the town of Montreuil-sur-Mer. He hated this position; the pay was a mere pittance, his fellow officers were corrupt, and worse, he was singularly struck with suspicion against a man that was nearly universally loved. This town had a new mayor, a man who had only arrived in the place several years before, yet singlehandedly revived its main industry and enriched the entire area along with himself. He went by the name Madeleine, and although he had his suspicions, it wasn't until Javert witnessed the mayor using his strength to save a man that his memory was stirred up. After this incident, he sent word to authorities that he'd found the delinquent Valjean. However, they informed him that this mayor couldn't possibly be him because the "real" Valjean has been captured. Javert, mortified, went to see the mayor and tried to tender his resignation, telling him the story of what he'd done, and how he'd made a mistake— an unforgivable offense in his book, for himself as much as for others.

"Monsieur le maire" refused to accept the police inspector's resignation; it did however open up a new dilemma for the former convict, the results of which didn't reveal itself to Javert until "Valjean's" trial, at which the mayor revealed himself to be the real Valjean. He immediately left for the hospital to visit Fantine, a woman who'd once worked at his factory and since been forced into prostitution. Javert followed him, and despite Valjean's pleas, refused to give him three days to ensure the woman's daughter would be cared for. With no choice he could see, Valjean promised he would take care of Fantine's daughter Cosette, then managed to escape from Javert. The inspector vowed to continue searching.

His next chance wouldn’t come until much later. The next nine years were uneventful, but eventually Javert's best qualities, namely his good memory and his doggedness, recommended him to his superiors, and he was transferred to Paris. Now, his path may cross again with Jean Valjean’s, even as the temperature of the city’s masses rises to a fever pitch.

-----

ALIAS: Levi

AGE: 26

GENDER: Female

OTHER CHARACTERS: none

HOW DID YOU FIND US: an ad on Caution 2.0

ROLEPLAY SAMPLE: (Note: this was written for another site and assumes the normal timeline of history. Also, he’s been thrown into the present day after his death.)

It was always a mystery to Inspector Javert, the excuses criminals would offer for their transgressions. They were supposed to be pebbles on the path to Justice, meant to trip him up, but instead he walked around them with sure and straight tread. There was only one path, one choice that he could see. So at Gavroche’s response he snorted. “You’re wrong. Better to miss a meal than to steal one. There is always another choice.” Gavroche probably thought he had never known starvation but he was wrong in that too. “Anyway, what of my hat, or did you plan to eat that as well?” he asked, eyebrows raised.

If there was one thing Javert could always afford to be, no matter where he was, it was discerning. It was just his way to be particular. Every button, every thread, every thought in its place. However, in their short walk to the library he could see the boy was right. There had been a few buildings that shared certain similarities with the architecture of Paris, but even those had a whiff of the strange about them, and they didn’t seem to be common either. So he nodded and said, “I take it the comforts here are small.” But there were comforts; any lingering doubts he had about this place faded by the minute.

Gavroche’s thoughts seemed to turn in the same direction. He admitted to liking it here, then made a crack about its government. The inspector surveyed the young boy without rancor or much of anything showing in his expression. It had never been about the students’ ideas, as such, but the chaos of change they planned to inflict on the land. Revolutions were a messy business. He should know. He’d grown up during one.

Javert hadn’t even seen the worst of it, not up close. He’d still been living in the Grand Châtelet at the taxpayers’ expense. By the time he was his own agent, most of the executions had taken on a legal flavor, except for those carried out by the mobs. The people were always hard to control; the trouble with Robespierre had been that he allowed this to happen alongside the legal proceedings. That was no way to run a country, republic or otherwise. To Gavroche the inspector said, “It seems stable enough. The streets are clean, the people look well.” If he sounded a little surprised, it was because the only republic he’d ever known hadn’t lasted a decade.

Grand-père? He caught up with the boy, not moderating his glare one bit. “Try it and I’ll call you chiot.” Some might think favorably of dogs, and in general so did Javert; but he was thinking of the strays that would lurk in the alleys and corners of the city, snatching morsels of food from passersby. Gavroche had their temerity, their penchant for biting the hand that might feed them. He’d certainly learned that in the fighting at the barricades, when he’d been the one bitten. Pity it hadn’t been a fatal wound. That would have been a more honorable death than the one he’d been forced into.

It was quiet in the library, but Javert had thought he’d spoken softly enough that they wouldn’t be overheard. Unfortunately, shamefully, he’d been wrong. Now he turned to face the consequences in the form of an irritated librarian. Javert didn’t quite understand what his mistake was exactly. She had heard him, yes, and he hadn’t meant her to, but the question was a legitimate one. From the way Gavroche was acting though, he could tell he’d erred somehow. He was even using the inspector as a sort of shield. Could she breathe fire?

It was a confused face he presented to the woman, but he returned to her desk and met her stern gaze fearlessly. It was also a face that put the lie to Gavroche’s lame excuse. He had the look of someone who rarely joked, and when he laughed, it was terrible. "Your trousers," he said without much deference— after all, he still was under the impression she was in the wrong. "You wear them so brazenly. Is there really no law against it here?"

And the shirt on your back doesn't keep out the chill